The dresses were extravagant in their use of materials. Using up to twenty yards of fabric, the cloths boldly reconfigured the feminine silhouette. Emphasizing a smaller waist and longer skirt, the new clothing eschewed the practicalities of wartime work and material deprivation. Yet simply wearing the one of the New Look dresses was work itself; the heaviest weighed sixty pounds and all required a tight girdled waist, limiting mobility.Dior's new look required structured bras and restrictive girdles. "Without foundations, there can be no fashion" Dior pronounce. Monchaux points out that very few women actually wore Dior's dresses, that like the Apollo spacesuit, "the massive impact of the New Look dresses was one of image."

Model skipping rope in a Playtex bra and girdle(1951); modeling the RX-2 "hard suit" (1965)

"I wanted to employ quite a different technique in fashioning my clothes, from the methods then in use" Dior would later write, "I wanted them to be constructed like buildings." And indeed, his dresses required restrictive foundational garments of highly structured bras and restrictive fitted girdles; the same technology that would be worn by the first men the moon two decades later:

The story of the Apollo spacesuit is the surprising tale of an unexpected victory: that of Playtex, makers of bras and girdles, over the large military-industrial contractors better positioned to secure the spacesuit contract... the expertise of Playtex in the craftsmanship and manufacture of intimate architecture would see its couturier-like sewing workshops produce a lunar suit that bested the best efforts of much larger better-funded military industrial proposals.

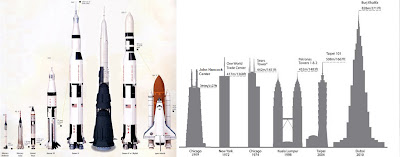

In February of 1949 alone, the New York Times discussed a "New Look" in materials (plastic), criminal justice (new streamline courts), infrastructure (new highways), and politics (changes in the structure of the Republican Party). "New Look" had become shorthand not just for fashion, but for all those things in the momentous shifts of postwar life, as Dior later observed, "we believe to be promising, [but] disconcert the public at first.The New Look of mental health was the application of "cybernetic" systems engineering by means of pharmaceutical drugs. In contrast to efforts to build environments suitable for the mentally ill, researchers were now turned their efforts on altering the brain to adapt it to the modern world - to create "cyborgs. The grimmest echoing of Dior however was Eisenhower's New Look. The restructured the American military industrial complex, away from new foreign deployments "in favor of a massive, nuclear arsenal. Monchaux writes, "Such a policy would reshape not only the size of the nuclear deterrent, but also its form, breaking the prior focus on strategic bombing in favor of a new delivery mechanism, the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM)."

When teams of of engineers from subcontractors gathered to assemble the missile system in prototype form, individual components were boxed, often in black, emphasizing and revealing only their connections to each other as a result the idea of a "black box" came to stand for the notion that one did not need to know how a subsystem worked, only its characteristics as it connected to other parts of the whole.

False heat test (1958); real football test (1967)

The choice of the the white Playtex designed A7L space suit over earlier silver models developed by engineering firms was a victory of fashion over antifashion, of soft power over hard, and craftsmanship over systems engineering, but also substance over style. Monchaux explains that the silvery fabric used on the outside of those earlier pressure suits was "nylon with a vacuum-blasted aluminum coating." The decision to use it had everything to do with style:

"Pretty glamorous looking." Then a light went off in my mind. "Say Dave why don't you make the outer cover of the pressure suit out of this material, in place of that awful-looking khaki coverall? ...A coverall of this material would look real good, like a space suit should - photogenic. to justify it technically we can tell them this silver material is specifically designed for heat or something."When the suit was unveiled at a photo-op a test pilot wore it surrounded by heat lamps to show the silver skins heat resistant properties. But when astronauts wore the suits they returned from there flights so soaked in sweat that the New York Times quipped that one of the great perils of space had turned out to be "dish wash hands." Subsequent suits were personalized with white fabric seats to make sitting in them for long periods more comfortable, but finally the silver covers were abandon and the decision was made to use the same fabric inside and out. "The high-temperature nylon provided a superior surface and did not run the risk of an astronaut dazzling himself with his clothing while facing unfiltered sunlight."

Angry Kids and Victor Ash, via The Fox is Black's Space Suit of the Week

But, that explanation has as much merit as the justification for making the first suits silver. Why not yellow, powder blue or International Orange? Monchaux writes that the ILC's Playtex-based technologies won out over the silver and hard suits that were then favored by engineers on merit of a single 16mm film:

For several hours - the length of a late-Apollo-EVE - the subject in a pressurized suit eschewed the the more technical motion studies of NASA's internal analysis for a full-fledged game of football - running, throwing catching passes and punting, falling and bouncing to his feet.

Monchaux observes that "For all the systems management efforts spent acclimating ILC to NASA's military-industrial milieu, the most heavily reproduced Apollo artifact - the ILC A7L spacesuit seen on stamps, in statuettes, and on screen - is in its essence a throwback, a regression, the sole exception to the rule." At a time when American power brokers were taken up with wearing stiff black suits, conceptualizing by means of rigid black box theories, implementing universal cybernetic control systems, and building the worlds talest skyscrapers severely black, brassier and girdle makers constructed a soft, white, aspirational object. (Continue Reading Part 6.)

No comments:

Post a Comment